A stock trader’s guide to navigating China’s curb on rare earths

A display of various rare earth elements in labeled containers, showcasing their distinct forms and origins, primarily from China. Stock image.

The names — holmium, europium, ytterbium, thulium, erbium — don’t show up in any of the investing classics. But they’re fast becoming an integral part of the Wall Street lexicon.

These minerals, and others in the category known as rare earths, are used to make advanced weaponry, cutting-edge computer chips and high-tech cars. And China, which controls some 70% of the mining and near 90% of processing, is curbing access to them.

The implications for investors are far-reaching, as countries led by the US scramble to shore up access to the raw materials, often by funneling investments to miners outside of China. End users, from ASML Holding NV to Ford Motor Co. to Hyundai Motor Co., likely will have to ensure supplies or pivot to technologies that don’t require them. The stakes are high, since lacking even a single input can snarl entire production lines.

Investors looking for clues on how to trade the new era got a small lesson in April, when Beijing slapped curbs on seven rare earths, gumming up some carmakers’ productions. Now, the broader restrictions stand to impact a bigger slice of the market, if they take effect in December.

“By increasing the number of rare earths subject to export controls, it’s likely to make the issue relevant to a greater number of sectors,” said Katherine Ogundiya, a thematic investing analyst at Barclays.

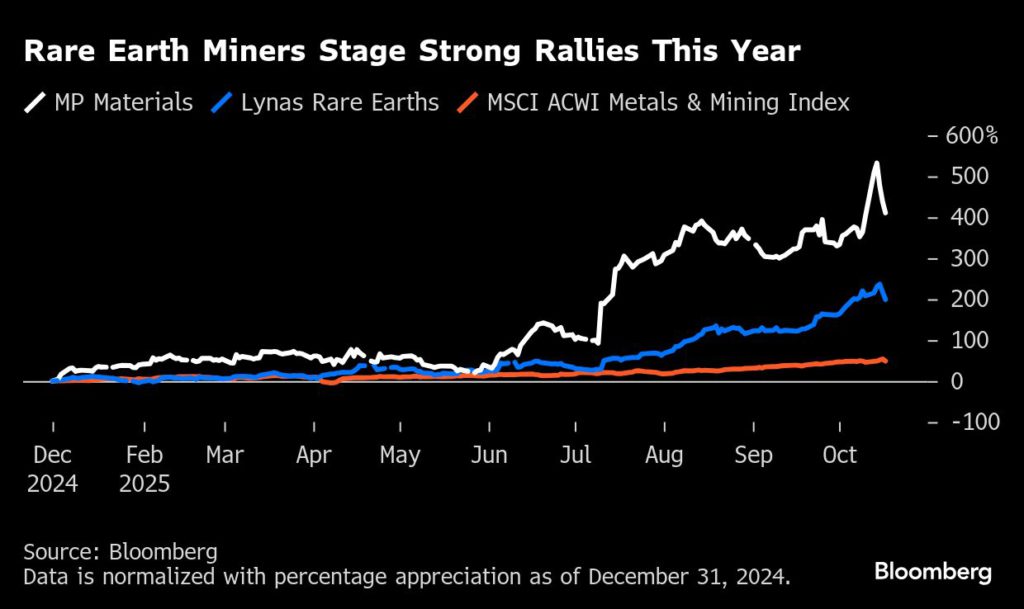

The issue is not just more metals will face curbs; the number of products subject to restrictions is also surging. That prompted a rush to shares of rare earth miners and processors, many of which have seen triple-digit gains this year.

Market reactions for rare earth users have been more muted so far, with traders speculating that China is using the new curbs as a bargaining chip. President Donald Trump tamped down his own rhetoric on Friday. But with tensions between the two superpowers showing few signs of easing, prudent traders have begun assessing just what might happen if the restrictions come into force.

Here are some sectors and stocks to watch:

Miners

Companies outside of China that can extract these scarce materials from the earth have already seen incredible share-price gains. In Australia, shares of Lynas Rare Earths Ltd., a major supplier backed by billionaire Gina Rinehart, almost tripled this year.

MP Materials Corp. soared over 150% since the US government took a stake that will help it expand production capacity. Shares of Critical Metals Corp., a Canadian miner that’s developing deposits in Greenland, rallied on a report suggesting the US was considering an equity position, which the Trump administration later denied.

Geopolitical tensions and deal speculations create a “security premium” for the sector, said B. Riley Securities analyst Ryan Pfingst.

Investors have to weigh whether gains can be sustained, and place bets on if Western nations will invest more in domestic champions. MP Materials remains loss-making. Lynas broke even in its most recent fiscal year, and analysts said it will take years for output to catch up with Chinese peers.

China’s miners have naturally benefited. Expectations for higher metals prices powered gains in shares of state-owned miners including China Rare Earth Resources and Technology Co. and China Northern Rare Earth High-Tech Co.

Semiconductors

The artificial intelligence boom has already made chipmakers the most important players in global stock indexes. Rare earths are critical to their production. A polishing liquid that contains cerium is used in a process to make wafers. Coatings made of Yttrium shield equipment components from corrosion. Lanthanum is added to many optical systems.

And China controls nearly the entire supply of them all, creating a potential choke point for chip equipment suppliers, according to Bank of America Corp. analysts including Didier Scemama.

While rare earths account for just a small portion of overall production costs for the chip industry, “to have that stop you is incredibly damaging,” said Willis Thomas, Principal Consultant at CRU Group.

That means companies like Applied Materials Inc., Tokyo Electron Ltd., ASM International NV and Lam Research Corp. could be at risk.

So far, investors haven’t grown skittish. BofA says current levels of strategic inventories should be sufficient for the next 12 to 18 months. The chip sector is trading near an all-time high following strong results at ASML and its top client, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. ASML said it’s “well prepared” for the curbs, and has materials for the “next couple of months.”

Defense

Weapons and drones can’t be made without rare earth elements. An F-35 fighter jet, manufactured by Lockheed Martin Corp., carries about 900 pounds of rare earth materials. A Virginia-classed nuclear submarine, built by General Dynamics Corp. and Huntington Ingalls Industries Inc., requires about 9,200 pounds. One drone motor contains between 12 and 60 magnets made from rare earth metals.

The question is whether these manufacturers can continue to access the minerals critical to production if the restrictions essentially block any rare earth exports to overseas military users.

“Even a few hundred thousand euros’ worth of parts can halt production given they often have only one supplier,” said Jens-Peter Rieck, an analyst at mwb research AG.

Investors will have to determine whether contractors get enough government support to justify already rising valuations. Rheinmetall AG jumped over 170% this year after Germany expanded its military budget. Lockheed erased yearly declines following speculation the US government might take a stake.

Automakers

A wide range of car components used in gas-powered and electric vehicles rely on rare earths. They are vital to parts like traction motors, sensors and braking systems, even though just a few hundred grams are needed in some cases.

China’s restrictions in April brought disruptions, with Ford temporarily shuttering a factory in Chicago in May because it ran short of rare earth components. That put investors in the likes of Toyota Motor Corp. and Volkswagen AG on alert for strategies that mitigate reliance on China.

BMW AG’s generation 5 and 6 and Renault SA’s E-Tech electric vehicle models are using motor technology that doesn’t require rare earth magnets, according to Morningstar analyst Rella Suskin. Indian automakers are also testing ferrite-based magnets, Bloomberg reported. Tesla Inc. laid out a plan to remove rare earths from its future models in 2023. Its Optimus robots would still need to use these elements.

Another strategy is to secure metals from suppliers outside of China. General Motors Co. has signed three domestic supply contracts for rare earth magnets, including a deal with Texas-based Noveon Magnetics Inc. in August.

Renewables

Like carmakers, wind turbine makers are diversifying their supply chain away from China, giving investors a metric to home in on. Siemens Energy AG signed an agreement in June to procure magnets from Japan’s TDK Corp. Australia’s Arafura Rare Earths Ltd. supplies both Siemens Energy and GE Vernova Inc.

Neodymium and dysprosium are two key elements for the wind power industry, and even without trade restrictions, analysts warn that the supply is at risk of being outstripped. About 10% of permanent magnets were used for wind turbines, according to a 2022 paper by the International Renewable Energy Agency.

While China’s new restrictions could push up metals prices, the industry has adapted well in the past, said Bloomberg Intelligence analyst Alessio Mastrandrea. He sees limited cost pressures on companies like Vestas Wind Systems A/S and expects any to be passed on to customers, if needed.

(By Henry Ren, Monique Mulima and Isolde MacDonogh)